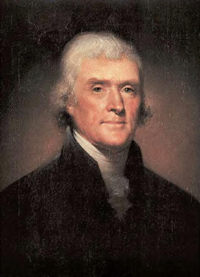

Thomas Jefferson attended William and Mary College where he studied math, science, literature, philosophy, and law. In April 1767, he was  admitted to the Virginia bar. He soon became known as a champion of independence from England. In 1775, he was appointed to the First Continental Congress, and in 1776, the Second Continental Congress which chose him to author the Declaration of Independence. He served in the Virginia House of Delegates, and he was the governor of Virginia during the Revolutionary War

admitted to the Virginia bar. He soon became known as a champion of independence from England. In 1775, he was appointed to the First Continental Congress, and in 1776, the Second Continental Congress which chose him to author the Declaration of Independence. He served in the Virginia House of Delegates, and he was the governor of Virginia during the Revolutionary War

After the war, he served in Paris as America's minister to France. During his absence, members of the Constitutional Convention contacted him, asking for his support of the new constitution. He gave that support, but only on the condition that the Bill of Rights be added.

When he returned from Paris, he served as President Washington's secretary of state until 1793. He ran for president against John Adams in 1796, but became Adams's vice-president, as the custom during those days was for the winner to become president and the loser to be his vice president. He ran again in 1800 and won, serving two terms as America's third president. While he was in office, he commissioned Lewis and Clark to lead an expedition across the Louisiana Purchase.

After his second term in 1808, Jefferson returned to his Virginia plantation, Monticello, where he worked as an inventor, scientist, architect, and linguist. It was during those years that he established the University of Virginia. Jefferson died on July 4, 1826, fifty years to the day after the Declaration of Independence was signed and. Coincidentally, that was the same day that John Adams died.

Raised Episcopalian, Jefferson believed that the New Testament had been polluted by early Christians eager to make Christianity palatable to pagans. He believed that they had mixed the words of Jesus with the teaschings of Plato and the philosophy of the ancient Greeks. The authentic words of Jesus were still there, he assured his friend, John Adams. He determined to extract the "authentic" words of Jesus from the rubble which he believed surrounded His real words. That book, intended as a primer for the Indians on Christ’s teachings, is commonly known as the "Jefferson Bible."

Written in the front of his personal Bible, he wrote:

"I am a real Christian, that is to say, a disciple of the doctrines of Jesus. I have little doubt that our whole country will soon be rallied to the unity of our creator."

In 1803, at the request of President Thomas Jefferson, the United States Congress allocated federal funds for the salary of a preacher and the construction of his church. That same year, Congress, again at Jefferson’s request, ratified a treaty with the Kaskaskia Indians. Congress recognized that most of the members of the tribe had been converted to Christianity, and Congress gave a subsidy of $100.00 a year for seven years for the support of a priest so that he could “instruct as many ... children as possible.”

On April 21, 1803, Jefferson wrote this to Dr. Benjamin Rush (also a signer of the Declaration of Independence):

“My views...are the result of a life of inquiry and reflection, and very different from the anti-Christian system imputed to me by those who know nothing of my opinions. To the corruptions of Christianity I am, indeed, opposed; but not to the genuine precepts of Jesus himself. I am a Christian in the only sense in which He wished any one to be; sincerely attached to his doctrines in preference to all others.”

In that same letter, he wrote,

“To the corruptions of Christianity I am, indeed opposed; but not to the genuine precepts of Jesus himself. I am a Christian, in the only sense in which he wished any one to be; sincerely attached to his doctrines, in preference to all others.”

In a letter to William Short on October 31, 1819, he wrote:

“But the greatest of all the reformers of the depraved religion of His own country, was Jesus of Nazareth.”